By: EB Dresser-Kluchman

Today, I’ve written on paper made from trees, and eaten ground–up legumes spread on ground-up, risen wheat grains. I’ve enjoyed the shade of ponderosa pines and the scent of sagebrush, eaten an apple and disposed of the seeds, and depended on my cotton bandana to keep the gnats off of my neck. I’ve also poured over seven hundred year–old corn kernels. Each of these ‘plant-based’ activities tell a story of who I am: what I like to eat, how I live my life, and the archaeology that I do.

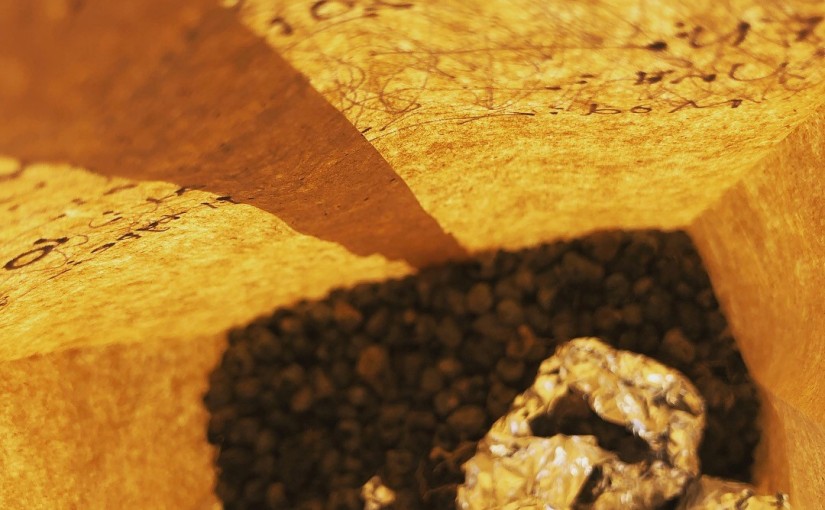

As a paleoethnobotanist, I study plant use in the past. Paleoethnobotanists study everything from whole fruits to microscopic phytoliths and starch grains. I focus on “macro” remains, which means I mostly study seeds and wood. These preserved over time by carbonization or burning. I spend a lot of my time in the field collecting charcoal from our excavation screens and running liters of excavated dirt through a flotation tank.

After pieces of charcoal have been pulled out of excavation screens and floated through our machine to remove them from the dirt, I will identify seeds, wood charcoal, and other plant parts. Knowing which plants are present at these Gallina houses will allow me to think about how people here dealt with them.

Plants are important in human lives and communities. We need to eat them in order to survive, but they are useful and meaningful in other ways, too. In contemporary New Mexico, green chile and red chile display personal preference and proud tradition. We use certain firewood because it’s available, sure, but also because it burns well or because it makes grilled meat taste better. We add spices and sweetening to our personal tastes, and the tastes of the people we feed. Whether in the city or the woods, we live with plants. Their smells, sights, and shade are the backdrop of our lives. To me, the oaky forests and ferns of New England will always be home, though I am now a more regular visitor to the ponderosas and cacti. The questions I ask depend on the assumption that plants meant something to people in the past as well.

So, how can we think about the relationships that Gallina people had with plants? What did they eat? What did they like to eat? What type of wood was right for building, and what type was right for burning? How and why did they include gathered food in their corn–rich lifestyles? We can’t ask them, but the charred bits left behind can say something.

First of all, Gallina sites, especially those that burned full of stored food, are packed with corn. Corn is a staple of the ancestral pueblo Southwest at large, but the density at these sites is exceptional. Also informative are the burned pieces of roof daub that we find in excavation and on survey with the bark of latillas and vigas still impressed in them. We’ve even seen evidence of agricultural terracing this summer on survey, which gives us a hint about how and where food and other domesticated plants were being grown.

Besides corn, we’ve also seen charred beans and a charred juniper berry in the excavation screens, but we’ll have to wait until I look at our flotation samples under a microscope to know more. I’m excited to learn more about firewood selection and to find out what wild plants and tasty seasonings entered Gallina hearths and storage. With a firm understanding of Gallina plants in hand, I can start thinking about how these plants took part in the lives of Gallina people—as tastes, traditions, sustenance, and so much more.

I don’t know a whole lot about archaeobotany or its subfields, but I have noticed that it is becoming more popular having attended a number of presentations in the last few years. Thank you for the introduction in to some of the activities of a paleoethnobotanist. The public is expecting big things from your field in the years to come. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person